The Lawrence History Center began its own history in 1978 when German immigrant Eartha Dengler came to Lawrence, MA. At that time there was scant interest in Lawrence's history. Families of the many earlier ethnic groups had been moving out of the City for two decades. The departure of most of the enormous textile mills which were Lawrence's economic engine and the subsequent displacement of ethnic neighborhoods during Urban Redevelopment resulted in significant loss of population even while newcomers were rapidly arriving from Latin America and Southeast Asia. Some of the impressive public and commercial buildings were razed, and other businesses were moving to surrounding communities or to the new suburban mall in Methuen. Public discussion emphasized the future; history was not the focus.

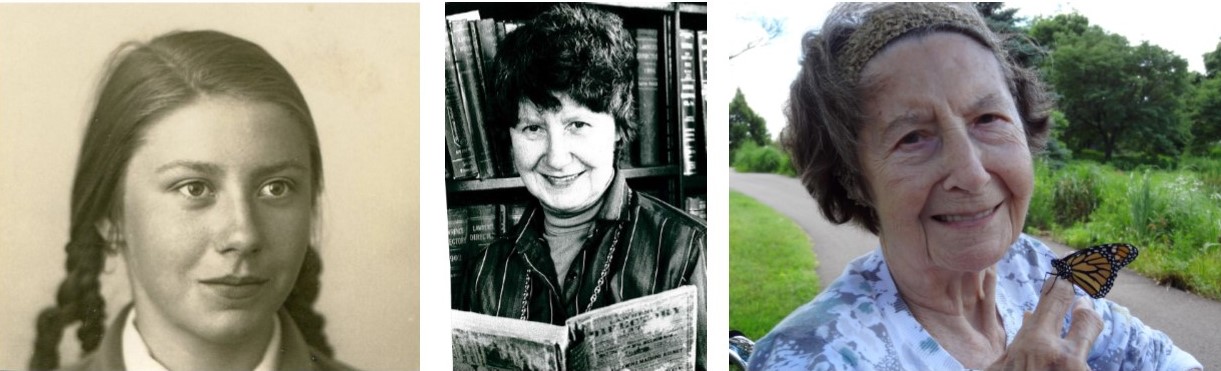

Into this environment came Eartha Dengler who had immigrated with her husband Claus and daughter Ann from war-ravaged Germany in 1951. Spending time in Chicago, she was struck by the cordial intermingling of the various immigrant groups, so unlike her experience in Germany of that time. It acquainted her with diversity and instilled a curiosity for learning about the backgrounds of different groups. Eartha and Claus became naturalized citizens in November, 1956.

Eartha realized how many immigrants like herself needed a place that would listen to their story and preserve their memories. Her life illustrates that one person, believing in her idea and in this city of Lawrence ~ understanding the need for a repository of preserved multi-vocal memory ~ can transform a commercial site into a place of memory and a place of pride for the City and her residents.

Eartha Becomes Involved With the YWCA

Located as it was in Lawrence, the Greater Lawrence YWCA served a rich mix of immigrant members. Organized by Protestant women to provide girls with leadership skills, it nevertheless embraced young women of various immigrant and religious backgrounds through its International Institute, and continued to do so after the YWCA and the International Institute separated in 1933.When Eartha came to the Lawrence area, she learned about the programs of the Greater Lawrence YWCA and was convinced to serve on the International Committee.

Click to listen to Eartha Dengler's oral history of the Lawrence YWCA.

Audio [1]: And this group met once a month to discuss other immigrant groups and usually the discussion was how different are Italians from Spanish or Spanish from Irish and I – and usually it was multinational – the groups hat met. And I had the idea that I would like to see how much we have in common. So I asked the group to sit down and go through a day and see how mothers in India have to get their kids out of bed as well as mothers in Germany and all the whole full preparation: clothing their children and all this – how many things are the same in different ways – done in different ways. But the worries when a child gets sick – do I send her to school, do I keep her home – is the same in Turkey as it is in America.

Audio [2]: There were lots of little lessons on the way to show me that a different nationality here, given the right incentive and the right climate of acceptance, could work together and wih almost comparative looking for the worst in the other person that had happened in Germany was – it happened here but wasn't promoted here. It was really interesting for me personally and also to bring these things to the attention of Y members – how exceptional they were when compared with other nations. That's when I started to look at their records how they had started because I had heard that the Protestant religion had played a large role in its development and still was not quite gone as a criteria for membership and also for the immigrant children. The Italians, for instance, lived around here where the YWCA was and how one of the priests tried to discourage their membership. And several Italian girls had told me they were taking their showers in the Y because there was no place for a decent girl to take a shower and it was only five pennies, five cents.

Eartha had already been gathering some records pertaining to the Germans and the Irish, but it was the YWCA records that gave shape to her interest.

Audio [3]: So it was interesting. And that's what piqued my interest in the Y as an organization and when the records became obsolete for them but they became important to me and I convinced them to turn them over to me and I would like to keep them.

Eartha Continues Her Efforts

While attending University of Massachusetts Boston, raising a family of three children (Claudia and Tom were born in the United States), working part time and, by the way, recovering from a fractured spine, Eartha set about developing the mechanism to capture Lawrence's history. She worked at what was then the Merrimack Valley Textile Museum (MVTM - later the Museum of American Textile History) as a weaving demonstrator on historic looms. After receiving her Bachelors Degree, she earned a degree in Library Science from Simmons College. With that in hand, she went back to work at MVTM. It soon became clear, however, that there was another story to tell about Lawrence that was not conveyed in that museum. MVTM's mission, according to the Director at that time, did not focus on the immigrant laborers, thus it declined the YWCA records. She then sought other options, including meeting with the Massachusetts State Archivist, who recommended that she organize a new history archives focusing on the special contribution of Lawrence to a broad array of American concerns, including immigration, ethnic interaction, labor and technology.

The Birth of the Immigrant City Archives

She gathered people knowledgeable and passionate about Lawrence history to create the organization, including Phyllis Tyler, Ednah Buthmann, Joseph Mahoney, Carolyn Hamilton, Thomas Leavitt, Andrew McCusker, Anita Moulton, Paul Hudon, and Peter Ford. Immigrant City Archives was organized on March 8, 1978.

Audio [4]: And so I – of course nobody knew of my idea and I just went on faith and charm and kind of tried to figure out who had an interest in history.

At first, the collections were housed in a small space in the YWCA. Eartha acquired a $5,000 grant from the National Historic Publications and Records Commission which was matched by a $2,000 grant from Jerome Cross of the Andover Bookstore and the Cross Coal Company and a $3,000 grant from Irving E. Rogers of the Lawrence Eagle Tribune. She remembers that her first purchase was a telephone. In 1986, the rapidly expanding holdings went to a large room in the South Lawrence Library branch, which made Immigrant City Archives far more accessible to researchers and to those wishing to donate items. Eartha was concerned that official City records were disappearing from City Hall because they were left in hallways and on the basement floor. She approached the mayor and City Council and they passed a resolution naming Immigrant City Archives the official City repository. Later on, learning that the Bessie Burke Hospital was slated for demolition, she went with volunteers into its basement and pulled out many boxes of records. From the earliest days, donors of photographs, books and documents would come in and want to sit down and tell stories about the items they were donating. This led rapidly to the practice of producing oral histories which, by 2007, had grown to 600 interviews.

Audio [5]: In fact, we had to convince people was interesting enough to be a historian. Because the answer we often got when we asked for an oral history – and which we started quite early the program – that “I was nobody important. I don't – I didn't have an interest in life. I just worked in the mills.” And so we really had to not only overcome the reluctance of the person doing research to focus on Lawrence, but to overcome the feeling of Lawrence people that whatever they had done in their life was of any importance to history.

Audio [6]: I always said oral history is important because immigrants do not leave written autobiographies or calendars or any written testimony of their having been in Lawrence. So for them to speak out and tell us about their lives is an important addition to our paper collection.

Acquiring the Essex Company

The South Lawrence Library Branch was seeking, even as Immigrant City Archives moved in, to increase its own collections and its hours, so Eartha began almost immediately after moving in to search for permanent space. Very soon she found the perfect spot: the former headquarters of the Essex Company, which built Lawrence. The current owner was sympathetic, but was trying to sell the complex for one million dollars, which the young organization could not possibly afford. Inside the headquarters were most of the records, tools and equipment of the Company. The owner was enthusiastic about donating these to Immigrant City Archives and agreed to continue to house them until he sold the property. He eventually sold the headquarters to Wilfred Cyr. Always on the alert, Eartha approached Cyr and asked if he would continue to house the records, and he agreed. But as Cyr sought to find an appropriate venture for the property, Eartha made clear to him what her hopes were. After several years Cyr sold the Essex Co. headquarters to Immigrant City Archives for $175,000, less than a third of what he paid for it. Moreover, he personally granted a $125,000 mortgage.

Audio [7]: It was a nice feeling to be in a building that meant so much to Lawrence history and has the content – has the documentation for all this because the documents reach back before 1845. And we have all the lamp shades and even a hutch and benches.

Eartha's Contribution

Among her gifts in developing Immigrant City Archives was Eartha's talent for gathering around her skilled and loyal volunteers. Many of these have worked for years to support her efforts to build the organization and the collections. Many gaps in the understanding of New England and even national history are filled because Eartha made this effort. When one compares the scholarship on the American Industrial Revolution before and after Eartha's establishment of the “Archives”, the difference in the awareness of and the perceived importance of Lawrence is remarkable. This is attested to by the hundreds of works – scholarly articles, books, radio interviews, newspaper articles and film productions that have referenced the organization. For Lawrence, the contribution of Eartha's work can scarcely be overstated. Certainly the thousands of people who have been able to connect to forgotten ancestors and who often choke back tears when they discover a family gem have Eartha to thank for the careful preservation of endangered records. The hundreds of voices that might have disappeared without notice now have made an enduring gift to history. And equally significant is the steadily growing appreciation of Lawrence by outsiders and by residents and former residents themselves. All of us who have come to love this city and to tell its story to others owe that capacity to Eartha Dengler.

Audio [8]: In my opinion, Lawrence is very much in need of a memory that creates a feeling of stability as a community that has grown from the early Lawrence in 1845 to what it is today. And it's grown in a very organic way and has – people can look back and see that they are part of an ongoing process.

A short clip of an interview about Eartha and her passion for civic life, America and immigrants, please view Eartha Dengler Receives "American By Choice Award"

In Memoriam: LHC Founder Eartha Dengler Passes at Age 91 (August 15, 1922 - March 8, 2014)

"I gave birth to my first child during an air raid while bombs were falling.

I came to America on a WWII freighter that was caught in a hurricane.

I chose my American name because I liked Eartha Kitt and Americans couldn't pronounce my real name, Erdmuth."

~ Eartha Dengler

Our founder Eartha Dengler passed away peacefully at home in St. Louis Park, MN on March 8, 2014, exactly 36 years to the day of forming the Immigrant City Archives, now known as the Lawrence History Center. Those who knew Eartha personally, as well as those who did not have that distinct pleasure, but who carried out her mission through their work at the Lawrence History Center are deeply saddened by this loss. As a community we will mourn and reflect on her leadership and vision – the impact of which on our “immigrant city” will be felt for generations to come. Eartha sent us these sentiments for our annual Eartha Dengler History Award Ceremony in June 2013:

“The story of Lawrence and its people is the story of America - of people pursuing a better life, of families taking care of each other, of hard work, of industry and of freedom. It's a story that most of us share. I am almost 91 years old and still the courage & fortitude of the people of Lawrence inspires me. When I started 'the Archives' I had a simple vision that the story of an American mill town & its people had to be captured & told. Truthfully - there were many days when I wondered if this goal of mine would ever be achieved. I am so thrilled to see how many of you share this vision. Through your efforts & contributions we have together collected, preserved and shared the story of the remarkable people of this community. I send my love & deep appreciation.”

Our thoughts and prayers are with the Dengler family. We will miss Eartha deeply. May she rest in peace.

Front page of Eagle-Tribune, March 10, 2014: Eartha Dengler, founder of the Immigrant City Archives, dies at 91, By Yadira Betances